Fast Act and Restaurant Jobs - Response to Beacon/Dr. Christopher Thornberg

Unfair comparison groups and an incomplete understanding of minimum wage policy affect the most recent attempted takedown of this law

Thanks so much for your support! Please remember to forward this email to one colleague you work with in this area. As the newsletter gets bigger, so does the input and overall quality. It all goes back to your support. Thank you!

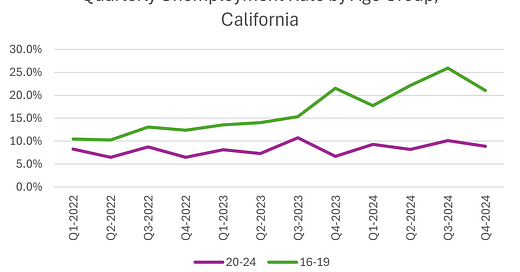

I was involved in an exchange with Beacon Economics’ Christopher Thornberg in summer 2024, over a report his team published on the Fast Act. The report focused on youth unemployment and argued that the Fast Act was increasing the unemployment rate of 16–19-year-old and 20–24-year-old workers in California.

I looked at the data myself and argued the statistics were too imprecise to say anything for certain. And for some groups, the implied effects were close to zero. I published a response and shared it with Beacon at the time. If you’re interested in that report, you can contact me.

On closer scrutiny and with more data 9 months later, Beacon don’t really have an argument on this front. Yes 16-19-year-old unemployment rates are up, but they have trended up for several years and so it’s hard to say the Fast Act is responsible. There was no sharp break in April 2024 (when the law went into effect) or the months leading up to it. And there has hardly been any change in unemployment rates for the 20-24 age group, or employment-population ratios (which are the preferred outcome here, since unemployment among 16-19 year olds is so rare to begin with! They have very low labor force participation for obvious reasons) for either group. See the charts below.

That’s not the reason for this post, however. Thornberg is at it again, with a new white paper out on the Fast Act, published through Pepperdine University’s School of Public Policy. It appears he has completely dropped the youth unemployment angle, and he is now arguing that the Fast Act caused job losses in the Limited-Service restaurant sector (NAICS 722513). See the new report here.

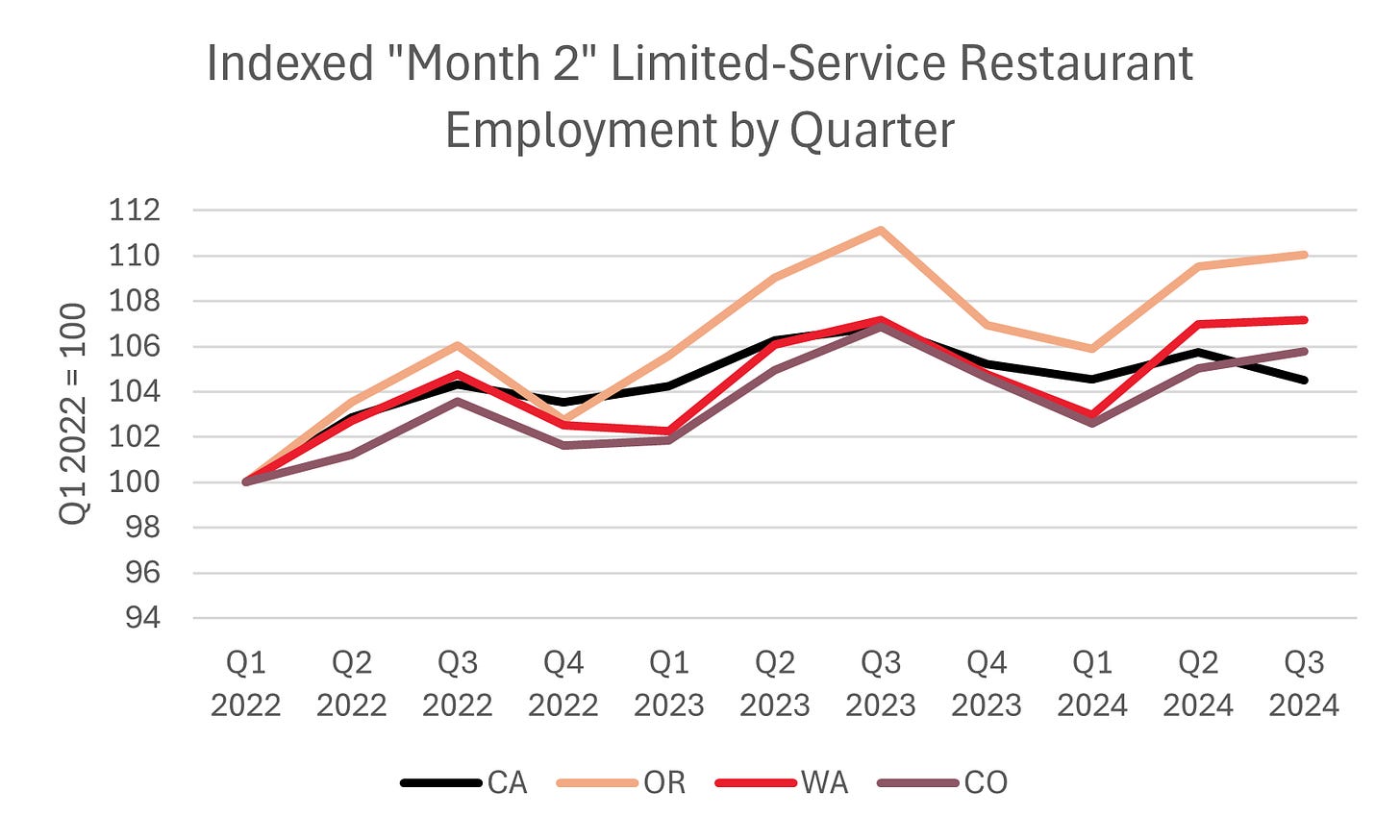

There are three points I will respond with. First, Thornberg makes a classic claim by comparing what’s happened in California to what has happened in the rest of the U.S. This is called a counterfactual: were it not for the Fast Act, California’s Limited-Service restaurant industry would have looked the same as it did nationally. But, this is a wrong comparison point. California, even without the Fast Act, is not like the rest of the U.S.:

Its minimum wage workers operate without a tip credit, meaning minimum wage workers’ earnings must start at minimum wage – this is different from most other states in the U.S.

California’s Limited-Service restaurants have significantly higher wages and a more dynamic labor market than the rest of the U.S.

When we make these adjustments to Thornberg’s comparison group, the implied job losses are much lower and do not coincide with the Fast Act. Other states, notably Oregon (high-wage market with no tip credit, like California), Washington (high-wage, no credit) and Colorado (high wage, but with credit - but very similar dynamics to California) have seen zero job gains or even year-over-year job losses similar in magnitude to California’s. See the chart below.

Second, Full-Service restaurants in California also had job losses – in California and the other states mentioned above. But Full-Service restaurants do not fall under the scope of the Fast Act. This suggests problems with California’s restaurant industry in general, that are not related to the Fast Act. See the chart below.

Notice how closely the two lines behave in that graph above. How could the Fast Act have had some independent effect, if a whole other group of restaurants not covered by the Fast Act - namely Full-Service ones - behaved the same?

Third, the Fast Act was also predicted to reduce establishments. Thornberg mentions this argument, but he doesn’t show any data. But the data are there. They show that establishments did not decline after the Fast Act. They actually grew by 4.3%/3.5% year-over-year, depending on whether you look at Limited-Service or Full-Service restaurants.

Thornberg’s second attempt at criticizing a law that already applies to such few workers, but which is meant to improve those workers’ earnings and offer them a better life, suffers from inappropriate comparison points, a misreading of the Fast Act’s targets, and an incomplete analysis of the data.

(Data in this post come from Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages through the BLS.)